The Fish Can Sing

Rekjavík from the Tjörn, Ca.1900, Frederick W.W. Howell, Cornell University Library

Darien’s review: The One Pure Note

On the shore of Lake Tjörn in Reykjavík, at the beginning of the 20th century, a coming-of-age tale unfolds. In this small, turf-and-stone cottage called Brekkukot, Álfgrímur Hansson views the world around him.

Álfgrímur’s foster grandfather, Björn, is a man with his own moral code, the foundation of which is absolute generosity. Bjorn wants for no more than he needs, and he shares whatever he has with those whose needs are greater than his own. Hence Brekkokot, though small, functions as a sort of refugee camp for the dispossesed. Álfgrímur himself is one of those refugees: his last name, Hansson, indicates that his father is unknown. His mother was on her way to America from somewhere in Iceland and left Álfgrímur with Björn.

Álfgrímur’s foster grandmother is yet another beneficiary of Björn’s compassion. After her husband and three children (all named Grímur) die, she comes to Brekkukot, and the elderly, unmarried pair keep house together. Álfgrímur’s natural mother wishes to name him Álfur, and his foster grandmother wants to call him Grímur (a reference to rímur--Icelandic poetic songs?), and so he becomes Álfgrímur. I don’t think that the grandmother’s name ever comes up in this book—she is a shadowy figure, as steadfast and integral as a beating heart. She is silent and nearly invisible, yet omnipresent. As little as Álfgrímur knows about her, so much more she means to him.

This Icelandic tale is told in the first person, which allows us not only to sympathize with the narrator, but also to feel his confusion, and to discover things along with him. Álfgrímur's outlook at the beginning of the book is typically childlike: he accepts his life, his fate, unquestioningly. He doesn't wonder why his mother left him, why his household is filled with itinerant people of little means, or why his family has few material possessions. In fact, there is no “why” to be answered, for he hasn’t asked the question. His life just Is.

As Álfgrímur becomes more aware of the people and the events outside the small world of Brekkukot, he begins to wonder and to question. The people around him don’t provide too many answers, which adds to the realism and charm of the novel. Aren't we all left to figure things out on our own, pretty much? And the answers we are freely given usually aren’t the ones we ask—or the ones we want. Álfgrímur’s first questions concern themselves with the enigmatic Garðar Hólm, who is a kind of cousin to Álfgrímur. Garðar acquired his name along with his fame as Iceland’s World Singer. He was born Georg Hansson; being fatherless isn't all that he has in common with Álfgrímur.

Álfgrímur has yet to understand the bond he shares with Garðar. As he and Garðar walk down Löngustétt,

Suddenly I felt a hand under my chin. “I thought it was myself,” said Garðar Hólm ... I gaped at him at first, tongue-tied, and finally replied, “No, it's me.”

As we read The Fish Can Sing, we ponder, along with Álfgrímur, what the Superintendent does for a living, the nature of the strange people who come to stay in the mid-loft at Brekkukot, whether we will ever hear Garðar Hólm sing, what will become of Little Miss Gúðmúnsen as well as the lovely Blær, the appeal of lumpfish, and whether the learning of Latin will benefit Álfgrímur. These questions, and so many more, flavor the book with a subtle confusion akin to being a very young man or young woman all over again.

As a librarian, I couldn’t help but relate to the description of The Icelanders' University, as enacted at Brekkukot:

From time immemorial it has been the custom in all sizeable farms in Iceland to have a good reader available to read sagas aloud or recite rímur for the household in the evenings; this was the national pastime. These evening sessions have been called the Icelanders’ University. Old people who had attended this university for eighty years or more came to know the curriculum pretty well...

I felt a sense of recognition at the feelings evoked in Álfgrímur by the woman who comes to Brekkukot to die. As she dictates to Álfgrímur, he comments:

This woman must surely have been descended from Snorri Sturluson. One thing is certain, that she never deviated from the most stringent standards of Icelandic prose style...Unfortunately, she failed to realize that one can set one's literary standards so high that it becomes impossible to utter a single word...

This is the fourth or fifth time I have read this book, and still discoveries awaited me. As many times as I have read about the Eternity Clock, which tick- tocks et-ERN-it-Y, et-ERN-it-Y (see the description of Laxness' own clock that it is modeled on) and despite my tears when I got to see it in person at Laxness’ home, this was the first time I really understood the concept of eternity that Laxness was describing. Álfgrímur considers:

How did it ever come about ... that I got the notion that in this clock there lived a strange creature, which was Eternity? ...It was odd that I should discover eternity in this way, long before I knew what eternity was, and even before I had learned the proposition that all men are mortal-—yes, while I was actually living in eternity myself.

I finally comprehended what Laxness was saying, and found it to be so profound. Isn’t this a defining characteristic of childhood: the feeling that time goes on forever? As children, we have no concept of the end of life. Childhood is the essence of eternity, and once we comprehend the concept intellectually, our eternity has ended—unless it should return upon our death.

Although I can’t read Icelandic, it appears to me that this translation by Magnus Magnusson is nearly perfect. It expresses both the story and the sentiments beautifully.

This particular work of Laxness’ is lyrical in its simplicity. To compare this book with his others is, to me, like comparing blues with jazz or with symphonic music. It is spare and lacks the complexity of his other works, yet has genuine depth. There is sweetness without sentimentality, and some of Laxness' familiar irony crops up—just not as frequently as in his other works.

The Fish Can Sing remains my favorite work by Halldór Laxness. Having reread it yet again I am surprised to find that my appreciation for his other longer, more difficult, more complex and ambiguous works, has grown. I have come to enjoy his other books so much more, over time. I suspect that, as I continue to reread his different titles, my Laxness Personal Ranking might be as changeable as a river. A characteristic of truly great literature is a dual process of transformation: the book is transformed in the mind of the reader, with each subsequent reading, and the reader is transformed by the book.

What does the One Pure Note mean to you?

Lækjargata, c.1900, Árni Thorsteinnsson

Caroline's discovery of an Icelandic coming-of-age tale:

Have you ever read a book and caught yourself smiling almost all the time? The Fish Can Sing is so charming I couldn’t help doing it. It’s also quite funny at times and certainly very intriguing. I’m afraid I can’t really put into words how different it is. As a matter of fact, Halldór Laxness’ book is so unusual and special that I have to invent a new genre for it. This is officially the first time that I have read something that I would call mythical realism. It is very realistic but, at the same time, it is full of exaggerations like we find them in myths. This is due to some extent to the narrator, Álfgrímur, who takes everything he hears literally. Very probably it also has its roots in Icelandic storytelling.

To give you an impression of how different it is, let me just quote the first sentence:

A wise man once said that next to losing its mother, there is nothing more healthy for a child than to lose the father.

This sets the tone nicely. This novel is full of unusual statements and observations. If you want to walk the trodden path when reading a book, chose another one. This is a wild landscape you are entering. A landscape of harsh beauty that—as I can only assume—must mirror the beauty of Iceland itself.

The Fish Can Sing is the story of little Álfgrímur whose mother gave birth just before emigrating to the US and left the baby behind at Brekkukot where he is adopted by the man and the woman he will call grandparents. His mother stayed, like so many others, for some time at the turf-cottage of Björn of Brekkukot. What a world this Brekkukot is. Dominated by the grandfather whose love for people, authenticity and truthfulness are the guiding light towards which so many are directed. The grandfather is the most important person in Álfgrímur’s life. He is the personification of absolute love and security.

"But whether I was playing in the vegetable garden, or out on the paving, or down by the path, my grandfather was always somewhere at hand, silent and omniscient. There was always some door standing wide open or ajar, the the door of the cottage or the fish-shed or the net-hut or the byre, and he would be inside there, pottering away."

"His constant silent presence was in every cranny and corner of Brekkukot - it was like lying snugly at anchor, one’s soul could find in him whatever security it sought. To this very day I still have the feeling from time to time that a door is standing ajar somewhere to one side of or behind me, or even right in front of me, and that my grandfather is inside there pottering away."

The grandfather is a real original. He follows his own rules and is not impressed by status or education. Álfgrímur feels that he is profoundly loved. The grandfather reminded me in some ways of Atticus Finch. Another culture, another society but the same aim for truthfulness and tolerance. Only a touch more eccentric. This novel is full of eccentric characters and unusual descriptions like those of the turf-cottage. The grandfather and his hospitality are so famous that people come from all over Iceland to sleep at the cottage. Some stay there always, some are on their way to the States, some are ill and look for a cure, others come to die there.

It would drive one mad to try to tell about all the visitors who ever came to Brekukkot, and indeed such a book would burst all the printing-presses in Iceland.

A dilapidated, creaking stair with seven steps connected the passage with the mid-loft in our house. It was here that I and my fellow-residents lived. This mid-loft was the centre-space of the upper storey, partitioned off from the rooms on either side; we were in effect a sort of vestibule for those who lived in the east and west ends of the loft as well as for anyone who went up or down the stair. When my grandfather did not give up his bed to a visitor, he slept in the part of the loft that faced south, but which was actually called the west end; otherwise he would lie on a pile of nets out in the store-shed, and would think nothing of it. Often our living-room was full, and people were tightly packed in at both ends of the loft; there were sleepers in the passage and sleepers in the doorway, and sometimes during the autumn trips, when we had the largest crowds, they would bed themselves down in the store-shed and the hayloft as well.

The book is told in a sequence of short chapters that could almost be read independently like short stories but it is still a novel. Some of the characters and stories that are told are quite funny.

It is a small and protected world in which Álfgrímur grows up and the outside world and foreign countries are only brought to his world through the figure of the somewhat mysterious Gardar Holm, a world-famous Icelandic singer who mostly lives abroad. There is a special connection between Álfgrímur and the singer and it is through him that he discovers his own voice and will choose to follow the same path.

The first real pain in Álfgrímur’s life comes from the need to go to school. To leave the safe haven of Brekkukot is terrible for him. All he had been dreaming of was staying there forever and becoming a fisherman. This can of course not be and the end part of the novel is therefore almost melancholic.

All in all, this was a great discovery. I really liked it a lot and think Laxness has a wonderful imagination.

Looking across Lækjargata towards Laugavegur, Reykjavík, c. 1900

Lisa’s Review "What’s it all about, Álfgrímur?"

This gem of a novel was my introduction to Halldór Laxness, and I am grateful for [my friend] Rose’s recommendation. I am also thankful that I came to the novel first with some small background knowledge of the sagas [editor's note: she's being modest]. Contemporary Icelandic literature and poetry have much in common with the medieval classics. I suppose that is because modern Icelanders can quote the sagas as easily as they do the day’s headlines (perhaps more so).

Álfgrímur (possibly from alfr, meaning elf, and grimmr, meaning fierce, although he is neither) is a character who reminds me a great deal of Forrest Carter’s protagonist Little Tree in the semi-autobiographical novel touted by its author as “A True Story.” Does this matter? No; I just find it interesting! I suppose both of these novels are “true” in some larger sense of the word. Both characters are young men raised by grandparents, surrounded by various colorful figures, who quietly take a stand against the accepted norms of society. Additionally, both characters often find that words are more of a burden, less of a gift.

I find this view of “words as problematic” intriguing since both books are written by men whose art seems more poetry than prose. For instance, at the beginning of Chapter 10, Álfgrímur observes,

At home in Brekkukot we did not acknowledge all the concepts which are now all the rage, and indeed had no words for them. All sorts of talk that was in common currency outside the turnstile-gate at Brekkukot struck us as mental illness; words which were commonplace elsewhere sounded not only strange to our ears but were downright embarrassing to us, like smut or other shameless chatter.

Later, he acknowledges that in his home,

… words were too precious to use – because they meant something; our conversation was like pristine money before inflation; experience was too profound to be capable of expression ….

Similarly, in The Education of Little Tree the young boy notes in Chapter 8 that his grandfather said:

“... if there was [sic] less words, there wouldn’t be as much trouble in the world.”

In fact, the old fellow

... favored the sound, or how you said a word, as its meaning.

A further explanation of love and understanding according to Little Tree’s grandparents is not to be missed. Like the pair of elders in The Fish Can Sing, Carter’s novel provides a tender example of marriage in its truest form between two tender hearts.

Hearts love well and truly in the Brekkukot cottage, although love is unspoken and affection is not demonstrated physically. Rather than being a cold home devoid of feeling, the stoic, independent and somewhat eccentric inhabitants create a loving family bond closer than most blood relations. Álfgrímur has no desire to achieve the world’s standards of success; to him, happiness is being a hardworking lumpfisherman.

Happiness is truth and authenticity in a well-lived life: the one, the elusive pure note of the novel, I believe. For Álfgrímur, happiness exists easily at Brekkukot. I would like to write more in support of this theme: of celebrity versus anonymity, of service versus servitude, of chasing after wealth versus contentment, of ribbons and bows versus the flowers of the field. Will Álfgrímur find happiness elsewhere following his travels on the mail-boat? With his moral compass firmly established, I have high hopes for him wherever he goes.

Reykjavík, circa 1900, via Gljúfrasteinn archives

Marthe looks at two old people left behind:

The fish can sing just like a bird

And grazes on the moorland scree

While cattle in a lowing herd

Roam the rolling sea

A reader should approach with caution any book that has won a whole bunch of awards. A reader should also approach, with all of their little brain cells firing at top speed, any book by an author who has won an international literary award for their work, like the Nobel Prize in Literature or the Man Booker International Prize. Finally, the reader should sit down and do some serious critical reading of such a book, without being overwhelmed by the author’s fame. So that’s what I set out to do with Halldór Laxness’ The Fish Can Sing. However despite all my caution, I was entirely disarmed by the book – I fell for its charm, and I was so taken with it that my critical thinking just ebbed away.

Darn that Sjón and his list of favourites! And double darn that old, dead writer Laxness for weaving his magic from the grave! What a thing to leave behind you when you die – not one, but 22 novels like this one, in which the beauty and the fascination can still grab and haunt the reader.

What is it about this novel, published in 1957, that still holds appeal for today’s readers? I was skeptical since I thought he is an Icelandic writer, and being from a small island with a small number of people (most of whom aspire to be poets) he might just be a big fish that can sing, in a little pond, pardon the pun. I thought of many “regional” authors whose novels are typical of their country or region and somehow have failed to transcend those domestic limitations. But that’s not this one, ladies and gentlemen. That’s not Laxness.

First, I thought it is just a precisely and cleverly crafted historical novel, set in Reykjavík, Iceland. It’s difficult to say exactly which period it is set in, since it covers decades – but I estimate it is round about 1874 to the start of World War I, 1914. The main character is a boy named “Álfgrímur”, who grows up as an adopted child in a poor family living in a little place called “Brekkukot”. The man he calls his grandfather, “Jón of Brekkukot” fishes for herring, cod, lumpfish and other fish from his little boat out at sea, and sells the fish from the wheelbarrow he pushes through town – an honest but not very profitable way to earn a living. The family’s house is really very small but is home to many people and guests.

“I must tell you that to the south of the churchyard in our future capital city of Reykjavík, just where the slope begins to level out at the southern end of the Lake, on the exact spot where Guðmundur Gúðmúnsen (the son of old Jón Guðmundsson, the owner of Gúðmúndsen’s Store) eventually built himself a fine mansion-house – on this patch of ground there once stood a little turf-and-stone cottage with two wooden gables facing east towards the Lake; and this little place was called Brekkukot.”

Every word counts

As is the case with many well-planned narratives, when I had finished reading it I suddenly realized the importance of that sentence, above, on page 1: it represents the social and economical disparity in Iceland at that time between the worker class and the upper or moneyed classes – the business people, educated people, academics, priests, government officials and people working for the Norwegian King and government. In this novel, every word, no matter how simple and plain, counts.

The working class people

The story is told from Álfgrímur’s point of view. He describes how he becomes a singer, so the novel is also about the “One Pure Note”, which people believe a truly great singer can achieve. There is no denying that Álfgrímur and his grandparents are poor, but they are decent and respectable, and interesting people come to live in the attic of their little house like permanent visitors, or they come there to die. Subtly, through various incidents and flashbacks, Laxness shows the reader that old Jón of Brekkukot and his wife are people who are truly honest and fair, and that they have no social aspirations and no affectations. They understand what people are at heart – they can see them for what they really are. They pass this uncanny skill on to their grandson, Álfgrímur.

The bourgeoisie and upper classes

On the other hand, there is the “Gúðmúnsen” family, who are the richest people in town, and who own the biggest store in town. I imagine that they live in Danish style, with their salt in fancy salt-cellars on their table, while the working class people just have the salt of the sea, and their salted, dried fish – it’s that kind of social dichotomy.

Many years before, the Gúðmúnsens realized that one of their butcher boys, called “Georg Hanssen”, son of a poor, single mother, “Kristín”, could sing. Or at least sing loudly. This boy becomes a world-famous opera singer, or so say the people of the remote island, Ísland, where he’s from. Judging from the newspaper articles coming from all over the world, he is the most famous exporter ever of Iceland’s culture, goes by the name “Garðar Hólm”, is incredibly wealthy, and travels the world in style.

The novel’s plot is largely about the mysterious Garðar Hólm and the fact that he somehow never sings where the people of Iceland can hear him. Álfgrímur proves that he too can sing, when he reveals his natural talent by singing at the burial of an unknown man, and so his grandparents send him away to get an education and learn music.

The mystery of Garðar Hólm

Does Garðar Hólm ever sing in the book? Is he revealed as a fantastic singer or a hoax or a mystery? Answering that would spoil the ending of the book, which quite took my breath away.

What I can reveal here is that the entire Gúðmúnsen clan is a nouveau riche bunch of money-grubbing, no-talent, pretentious people. At the final big event in the book, the store owner, “Björn Gúðmúnsen”, tries to show off his German skills, since all things Danish and German were considered to be very posh at that time. He throws German phrases into his speech but in fact he is saying something random and silly that you would find in a German grammar book. With reference to the need to show off Icelandic art and skills, he says “er ging in ein Wirtshaus hinein um zu Mittag zu essen” – meaning “he went into a tavern to have lunch”. Or when toasting his wife, “er setzte sich an einen Tisch und nahm die Speisekarte”, which means “he sat at a table and picked up the menu”. None of his family members or his guests have any clue he is spouting baloney.

In Ísland people want the fish to sing

Laxness slowly immerses the reader into life on the island, where everything in the big outside world is viewed as fabulous and desirable, and every thing and person on the island itself as mediocre and in need of titivation. For that reason, the wealthy people tie bows around every object in their houses, even the pets.

This explains the title of the book. The store owner and main man in town, Björn Gúðmúnsen, says:“…salt-fish has to have a ribbon and bow. And it isn’t enough that Icelandic fish should have Danish ribbons and bows; it has to have the ribbon of international fame. In a word, we have to prove to the rest of the world that ‘the fish can sing just like a bird’. And that is why we who sell the fish have made great efforts to improve the cultural life of the nation to show and prove, both internally and externally, that we are the people who not only haul the grey cod out of the depths of the sea but also tie a ribbon and a bow around its neck for the delectation of the world…”

What a stupid idea. The unadorned, un-singing fish, and the people who fish them, are good enough as they are. What the wealthy people of Reykjavik effectively achieve with Garðar Hólm is to put bows and ribbons on him, like with a fish, and he sings, like a fish. Or not. But that’s for you to find out.

Not pastoral – scathing

This realization emerged slowly as I progressed through the book, and what I also realized is that this charming little historical novel, which is devoid of sex, murder and mayhem, and seems so pastoral, is not so innocuous at all. It is an intense, scornful condemnation of the Icelandic politics of that time:- the slavish obedience of Danish rule, the veneration of all things Danish, German and foreign, the lack of respect for independent, poor, working-class people, and the lack of faith in the future of an autonomous Iceland. I wanted to laugh at the silliness and stupidity of the people but at the same time it made me feel sad and a little put off.

Laxness himself made his point of view quite clear in his speech when he accepted the Nobel Prize:

“As I was sitting in my hotel room in Skåne, I asked myself: what can fame and success give to an author? A measure of material well-being brought about by money? Certainly. But if an Icelandic poet should forget his origin as a man of the people, if he should ever lose his sense of belonging with the humble of the earth, whom my old grandmother taught me to revere, and his duty toward them, then what is the good of fame and prosperity to him?”

All the right words for love

Laxness not only excels at the depiction of a lifestyle from when he was a young boy and Reykjavik was not yet a big city – I could so clearly see every scene in my mind’s eye. What he is really good at is depicting the core of people, their inner lives and their emotions. He uses all the right words to describe love in all its forms. He is particularly skilled at describing Álfgrímur’s grandparents. When the store owner Björn Gúðmúnsen offers to pay for him to go and study music overseas, to become another Garðar Hólm, his grandfather refuses the money, and his grandmother explains:

“…as far as Gúðmúnsen’s money is concerned, it has never been valid currency with us hitherto. Besides, I would have thought that the same thing applied to singing as has been said about poetry here in Iceland: ‘I write for my own contentment and not my own aggrandizement.’”

“One should create art for one’s own contentment and not one’s own aggrandizement” is probably the moral of this story.

To finance Álfgrímur’s overseas tuition, and believing in his talent, his grandparents decide to sell their little house (see, that’s why that introductory sentence matters) and see him off at the harbour. At this point, I confess I had a big lump in my throat. Laxness knew how to move his readers emotionally with few, simple, direct words. I think I’ll always remember this scene.

Lækjartorg, c. 1903

Stephen’s serendipitous discovery:

I recently realized that I had once spent eight days In Iceland within a thousand meter radius of my apartment.

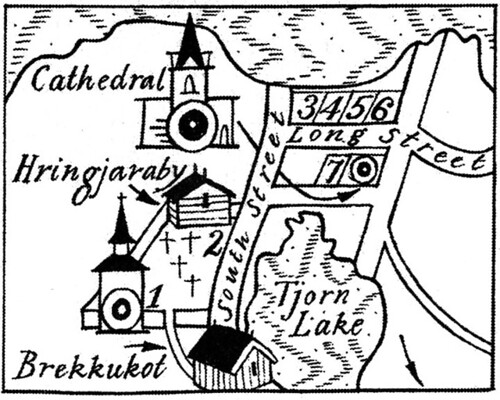

A very small world, to say the least. Waking to the sound of the Cathedral bell, going out at night to the venues of the Airwaves festival, shopping, and even swimming at the outdoor pool, all within a small area. While shopping, I had picked up some books at Máls og Menningar, mostly titles which were not distributed in the USA. When I returned home I started reading The Fish Can Sing (Brekkukotsannáll) and on the first page I found a small map:

This map was of nearly the exact same area I had inhabited during my stay.

The Fish Can Sing (originally published in Icelandic in 1957 as Brekkukotsannáll) is probably the most accessible Halldór Laxness novel. This coming-of-age story centers on the orphan Álfgrímur and his relationship to his very small world. This small area is, however, rich in characterization and momentous events. Each of the episodic 41 chapters exposes Álfgrímur to some new lesson about life; lessons which he takes to heart as he comes to grips with the modern world and his role in it. Gardar Holm, a “world famous” singer (who may be Álfgrímur’s father), appears from time to time. In a sense, he represents Laxness himself; a world traveler who is not exactly what he seems. Álfgrímur may be thought of as personifying Iceland at the turn of the twentieth century, waking up from a solitary existence, ready to go out and make a mark in the world. Gardar’s talks with Álfgrímur exist with several levels of meaning: personal, artistic, political, moral and emotional.

The tone of the book is generally lighthearted and it is quite funny at times. The characters who drift in and out of young Álfgrímur’s life ground it; their faults and foibles reveal basic human dignities. All in all a wonderful book, the translation (by the esteemed Magnus Magnussson) seems to capture Laxness’ deceptively simple style; certainly well enough to completely charm this reader for the third time! This book is a work of fiction, of course, but the locale of the story’s action could not have been any closer to my own explorations if I had written it myself. After the Airwaves festival was over, I spent a few more days in town with much of that time photographing the various neighborhoods (all within 1000 meters of my apartment, naturally.) One night I shot this view of the old graveyard on Suðurgta (South Street on the map):

According to the book's map, the hut Hringjaraby (where a crucial scene took place), would have been right at the center of my picture.

A very small world, indeed.

Hafnarstraeti, 1910, Via Lemúrinn, photographer unknown

William’s essay on One True Note:

A genius of a book. A brilliant book. A book that grabbed my heart.

How could I, coming from Gimli, with some Icelandic genes and a lot of Icelandic history and culture, not have read this book before now? It makes one wonder about the waving of flags and toasts to Iceland and speeches and Viking helmets and all that and just how meaningful it is when someone like me hasn’t read The Fish Can Sing by Halldór Laxness.

How many North Americans of Icelandic descent have read The Fish Can Sing? Raise your hands. I think I’m going to ask this question at next year’s Islindingadagurinn. That way I won’t feel quite so guilty. Guilt likes company.

I have excuses. I lived in Iowa, Missouri, British Columbia. None are hotbeds of Icelandic culture. But I’ve never missed an Icelandic Festival and never turned down a piece of vinarterta. Surely, part of that experience should have included reading stories by Laxness. He’s the only Nobel prize writer we’ve got. It’s not like Laxness’s books aren’t available. Tergesen’s always has them on sale and you now can buy them on Amazon. They’re not expensive.

This is an easy book to read. For one thing, it is a happy book. It’s about a little boy without a father and whose mother, when she leaves for America, hands him to an elderly couple. The couple at Brekkukot treat him in every way as a beloved son.

The narrator is that boy grown-up. He explains that since he has no father, his last name is Hansson which means “His-son.” There is no man’s name, Arni or Baldur or Ragnar so that he could be called Arnis-son, Baldurs-son, or Ragnars-son.

The couple who take on the role of both parents and grandparents but are neither, they’re not even married to each other, and do not just feed and clothe him but provide him with a set of moral values, with security, with an education and, finally, with an opportunity to rise in the world.

Brekkukot is just a fisherman’s cot but it also is a place of refuge. People who need a place to stay come there, sometimes staying for years on end. These visitors help to provide the boy, Alfgrimur, with an education. People come to get well, others to die. The property lies beside a graveyard and it is here that Alfgrimur hears singing and eventually sings over the graves of those who cannot afford to pay someone to sing for them.

Nearby lives an elderly woman, younger than the woman he calls grandmother, but nearly blind and deaf. She has a son who has become famous as a singer in Europe and who has the stage name Gardar Holm. Many people assume that Alfgrimur and Gardur Holm are related but the relationship is never defined. Gardur Holm takes an interest in Alfgrimur, buys him cakes, gives him money, counsels him.

The book is about fishing for lumpfish, about eating cream cakes, but it is mostly about poor Icelanders who are presented in a way that is dignified, that makes them human, that allows them to be proud in spite of their poverty. These are people who are honorable and, who, in spite of a lack of formal education, ask profound questions.

Alfgrimur gives us a picture of his grandfather, Bjorn of Brekkukot, that brings him to life. Here was a man who was never heard referring to anything contained in the sermons but wouldn’t accept even a Bible without paying for it. When a neighbour steals precious peat from him then, with a guilty conscience, brings it back, Bjorn invites him in for coffee, discusses what has been done and ends up giving the peat to the thief.

Bjorn would not have been out of place in New Iceland. I recognize him. As a child, I knew rough fishermen, usually stolid and silent, strong, even hard but they, too, seeing someone with less than them would have given the thief wood from their woodpile.

This book is a delight because of the sympathetic descriptions of the people with all their oddities and foibles. However, it also raises serious questions about the purpose of life and the way it is lived. Bjorn ignores the marketplace. He does not lower his price when there are fish in abundance, nor does he raise his price when there is a scarcity of fish. To him, fish have a value whether they are abundant or scarce.

Gardur Holm is presented as a world famous operatic singer. He appears and disappears, always with rumours of his success swirling around his visits. Gradually, though, the facade that he presents is shattered. At a dinner in his honour that ironically is really about the success of the merchant who has provided the money for Gardur Holm to go to Europe and to have a singing career, the merchant says that “it isn’t enough that Icelandic fish should have Danish ribbons and bows, it has to have the ribbon of international fame. In a word, we have to prove to the rest of the world that ‘the fish can sing like a bird’. And that is why we who sell the fish have made great efforts to improve the cultural life of the nation”.

But Gardur Holm in talking to Alfagrimur tells him a story that reveals what his life has really been like. The grant of money is seldom much and it often doesn’t arrive. It is the story of artists yesterday, today and tomorrow. It is the story of artists in a society that values fish and profits or aluminum smelting and profits or banking schemes and profits over all else. The artist, as Gardur Holm describes him, is a poor wretch desperately clinging to the small gifts given by the merchants of fish (or, if you wish, the Canada Council.)

At the beginning of the book, the narrator says, “I think that our own standard had its origins in my grandfather’s conviction that the money which people consider theirs by right was unlawfully accumulated, or counterfeit, if it exceeded the average income of a working man; and therefore that all great wealth was inconsistent with common sense. I can remember him saying often that he would never accept more money than he had earned.

“But what does a man earn, people will ask? How much does a man deserve to get?”

This book was first published in 1957. How more relevant could it be to a society that has been told that greed is good? A society where bankers steal a good deal of people’s money and lose the rest through incompetence, where bonuses are obscene and retirement packages beyond all reason? Where a small percentage of the population takes more and more of society’s wealth?

The questions and objections being raised by the Occupy movement and others, even the President of the United States and the Prime Minister of England, are all here. For those who are prepared to fight for social justice, a picture of Halldor Laxness on their flag would not be amiss.

This is a book to enjoy but it is also a book to ponder.

Women driving cows, Reykjavík, 1910, Via Lemúrinn, photographer unknown

William, again, on The Economics of Halldor Laxness in Fish:

In The Fish Can Sing, Halldor Laxness presents through the narrator Álfgrímur the economics of Björn of Brekkukot and, thus, his own economic philosophy.

Björn is a lumpfisherman. He lives on a small piece of land and, with his fishing, supports himself, the woman who shares the house with him and the child, Álfgrímur. He does not go far from shore seeking cod, nor does he fish the rivers for salmon. He doesn’t seek to maximize his catch nor as the modern term goes, monetize it. He does not dream of having a larger boat, of having many hired men instead of one or two, or increasing his profits. He does not have the ambitions of a modern day banker or businessman. Björn is interesting precisely because, while he is created as a fully realized character in the novel, he also represents a set of ethical principles, particularly with regard to money and how it is earned.

On the first page, as one of those simple details that might be dismissed as only being about backstory or setting, Álfgrímur tells us that “… on the exact spot where Gudmundur Gudmunsen (the son of old Jon Gudmundsson, the owner of Gudmunsen’s Store) eventually built himself a fine mansion house—on this patch of ground there once stood a little turf-and-stone cottage.” With no ado, no sign posts but in a quiet contrast, the conflict between values the reader will see throughout the novel is set. The values are represented by the cottage versus Gudmunsen’s store. There is a little fillip added with Gudmunsen’s Store being spelled the Danish way so that we are gently nudged to understand that these values will be Danish values, learned in Denmark as opposed to the values of the authentic Icelandic farmer.

It is also significant that it is the simple Icelandic peasant cottage that has been replaced by the mansion built from profits made by the Gudmunsen’s store. In another of Laxness's novels, Christianity Under Glacier, the house of Godman Singman has been built on church property, overshadowing the neglected church building. In both cases, the amassing of money has overtaken Icelandic values, both secular and Christian.

It is, of course, not just Laxness that makes this distinction. Charles Lock, in The Home of the Eddas (1879), makes a similar point. He went to Iceland in 1875 and spent twelve months there. He says, “Circumstances compelled me for the most part to shun the principal cheapsteads, such as Reykjavik and Aukeryri, where the life of the people are half Danish, half Icelandic, and threw me among the pure-blooded bondar and peasant classes.”

Álfgrímur, the narrator in The Fish Can Sing, tells the reader that “The rest of the town’s inhabitants were cottagers who went out to the fishing and sometimes owned a small share in a cow or had a few sheep.” This is the large amount of the population who live in opposition to and are exploited by the well-to-do farmers who are aligned with the Danish overlords.

In the spring when Björn went lumpfishing, he sold his fish from a wheelbarrow. He boils fish liver for the oil, makes do with what produce the family can manage to produce. We've been told that the cot has peat pits as a preliminary to Álfgrímur recounting an anecdote about a man coming to Brekkukot with a sack over his shoulder. The sack contains peat that he has stolen from Brekkukot. Fuel in Iceland is always in short supply. It is carefully husbanded. The thief’s crime, in a place where there is so little fuel that it is often hard to find enough to cook food, is serious. Björn has already given this neighbour peat. Now, Björn asks the thief in to discuss what it is that he has done. He tells him his actions are wicked, but after coffee, he gives the neighbour the peat.

One is reminded of the scene in Les Misérables when the police bring Jean Valjean’s back to the home of the bishop who befriended him. Jean has returned this kindness by stealing of some silver candlesticks. The bishop says Jean didn’t steal them, that he had been given them.

For a period of time, Laxness became a Catholic, then a Communist. Both outraged both his countrymen and people of Icelandic descent in North America. The question is when Björn forgives the peat thief and gives him the sack of peat is Laxness, through Björn, acting as Catholic or Communist? Álfgrímur would doubt both for he says that his grandfather was “a man of orthodox beliefs” but not one to cite scripture or to ask God to do anything. Any forgiveness that was given came from Björn. He also did not forgive in the name of the state, particularly a state that adhered to a philosophy that denied individualism, and Björn forgives as an individual.

Early in the book, when the principles upon which it will be based are being created, Álfgrímur describes the standards by which life was lived at Brekkukot. He says, “I think that our own standard had its origins in my grandfather’s conviction that the money which people consider theirs by right was unlawfully accumulated, or counterfeit, if it exceeded the average income of a working man and, therefore, that all great wealth was inconsistent with common sense.”

Shortly thereafter, Álfgrímur says that his grandfather believed “… that the right price for a lumpfish, for instance, was the price that prevented a fisherman from piling up more money than he needed for the necessities of life.”

These are simple beliefs and are obviously not believed in a society where someone can say out loud “greed is good” and not become an automatic laughing stock. Björn of Brekkukot, today would see that it is the Danish traders’ belief that the price of lumpfish should rise and fall with supply and demand that has triumphed, that economic values dominate all other values, including the values of democracy. This belief in the right to make money prevailing over all other values carried Iceland not just to the brink of collapse but to collapse itself. It is only by open revolt against such avaricious, materialistic principles by the banging of pots and pans outside of Parliament, the repeated public demonstrations, the actual physical rebellion of Icelandic society that has driven out the bankers. It is those people who had values more in line with Björn of Brekkukot who finally rebelled against the values of Gudmunsen’s store, against the values of another Björn, this one, Björn of Leirur, in Paradise Reclaimed.

It is, of course, precisely these values of Björn of Brekkukot that made Laxness the object of investigation by the FBI and the enemy of many in the Icelandic North American community for what is the opportunity of North America but the opportunity to make money? And what is the person who would question that right but the enemy?

Who in North America today defends those who are the equivalent of people who sometimes own a small share in a cow, or have a few sheep or own a small rowing boat? The political struggle in the Congress and the Senate, in the Canadian Parliament, is among the privileged as to who gets the greater percentage of the spoils, not between the defenders of ordinary people and the privileged one percent.

In spite of the growing disparity in wealth in North America between the privileged few and the larger society, there still exist those who believe as does Björn of Brekkukot. Just the other day a relative of mine, offered a sum for some old books said no, the price was too much and she named a lower price and said this is what they are worth. The books, like lumpfish, had a price unrelated to what the market might pay at any given moment. And I, in one of my short stories, many years ago, wrote of a fictional character based on my father who when offered fishing equipment by a friend who was a terrible drunk, always bought it but, when fishing season came around again, always sold it back at the price he had paid and of the disaster created when the equipment was bought by a lawyer from the city who saw only an opportunity to make a quick profit. The values of Halldor Laxness, of Björn of Brekkukot, is what creates a decent society. This is the fabric of a society where human failure is recognized as inevitable and not exploited. This is a society where forgiveness is more important than punishment.

Laxness would in his own way preach that society is not governed by tooth and claw, that it is not a collection of predator and bloody meal, of exploiter and exploited. Or, at least, that it does not have to be. How subversive is that?

During the time Denmark ruled Iceland, the Icelandic employees of the Danish merchants treated their fellow Icelanders abominably; they passed on Danish contempt. It was a lesson rubbed into the very grain of Icelandic society and was still in the grain in 2008. It is what allowed the bankers to disregard the welfare of everyone in the country except their own welfare. You can only enrich yourself while destroying your family, neighbours and society if you hold them in utter contempt. You can only get away with doing it in a society that has been brain-washed to believe that the values of Gudmundsen’s store and Björn of Leirur are the only values that matter.

It is time, even past time, that Icelanders began to read Laxness again and listen to what he had to tell them. Then they might answer the question, who is right, Björn of Brekkukot or Björm of Leirur along with his disciples, the bankers of America and the EU?

Laugavegur, Reykjavík, c. 1900, via Gljúfrasteinn archives

Brad discusses ‘Laxness the Great’ re: Fish in The New York Review…

Michael's Complete Review of Fish…

Stella compares Fish to Satanic Verses…

Brydon compares Fish with Hamsun's Growth of the Soil…

Richard’s L.A. Times Review of Fish…

Kate’s appreciation of Fish…

Dagny’s review of “The best book that’s ever been written,” and a personal Laxness meeting (in the comments)…

Neil's “Impressions” of Fish…

David’s dissertation on TFCS …

Bruce praises one of his “favorite” books and its translator…

Victoria compares Fish to IP…

Wood’s slow read of Fish…

Jack takes a look at “mythic” Fish…

Macaroni uncovers gems of wisdom in Fish…

Derek, Andy, and John ruminate on Fish in a podcast, (Fish content starts 18:00)…

Sjón lists his 10 favorite books…

Time Magazine’s 1967 review on Fish…

New Persian translation of Fish…

Publishing history:

Brekkukotsannáll, Helgafell, Iceland, 1957

Translated by Magnus Magnusson:

Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, 1966

Thomas Y. Crowell Co, New York 1967

Harvill Panther, London, 2003

Vintage, Random House, New York, 2004

Penguin paperback, 2022, eBook, 2010

"His constant silent presence was in every cranny and corner of Brekkukot - it was like lying snugly at anchor, one’s soul could find in him whatever security it sought. To this very day I still have the feeling from time to time that a door is standing ajar somewhere to one side of or behind me, or even right in front of me, and that my grandfather is inside there pottering away."

A dilapidated, creaking stair with seven steps connected the passage with the mid-loft in our house. It was here that I and my fellow-residents lived. This mid-loft was the centre-space of the upper storey, partitioned off from the rooms on either side; we were in effect a sort of vestibule for those who lived in the east and west ends of the loft as well as for anyone who went up or down the stair. When my grandfather did not give up his bed to a visitor, he slept in the part of the loft that faced south, but which was actually called the west end; otherwise he would lie on a pile of nets out in the store-shed, and would think nothing of it. Often our living-room was full, and people were tightly packed in at both ends of the loft; there were sleepers in the passage and sleepers in the doorway, and sometimes during the autumn trips, when we had the largest crowds, they would bed themselves down in the store-shed and the hayloft as well.

And grazes on the moorland scree

While cattle in a lowing herd

Roam the rolling sea

0 Comments:

Post a Comment