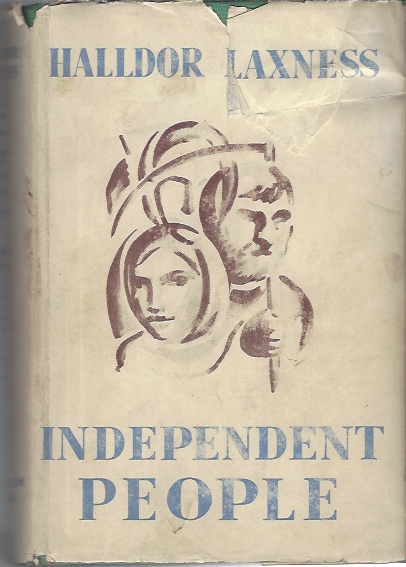

Independent People

Haying, Iceland, 1911, Magnús Ólafsson, Cornell University Library Collections

Abi reviews her “best” book:

“How much can one sacrifice for the sake of one’s pride? Everything, of course - if one is proud enough.” - Halldór Laxness, The Atom Station, 1948

No less than the best book I have read so far in my life.

Independent People (original title: Sjálfstætt Fólk) is the tragedy of a man who is proud enough to sacrifice everything. It tells the story of Bjartur of Summerhouses, his family (especially his daughter, Ásta Sóllilja) and the ‘world war’ they wage against the harsh Icelandic landscape in which they live and the demons, imaginary or otherwise, that inhabit it. Bjartur has spent 18 years scraping together enough money to buy his own croft (a croft that is supposedly haunted by a ghost destined to bring failure to all who try and farm there) and is determined at all costs that he and his new wife Rósa will live as independent people.

He is stoical beyond belief, often frustrating the reader to tears with his stubborn refusal to deviate from his principles, to the detriment of his wives and children. He is callous to the point of cruelty and yet not unloving, and this for me was the most heart-wrenching strand in the novel (portrayed most clearly in his relationship with Ásta Sóllilja, but present throughout). It isn’t at all that Bjartur doesn't experience love; it’s that his misguided desperation for independence forces him to suppress his own humanity. And, in fairness, clinging to his principles must have been the only thing that prevented him from being crushed. He simply cannot allow himself to feel, otherwise he would sink beneath all that death and poverty. Set in the late 19th and early 20th century, superficially this is a book about sheep farming and drinking coffee, but in reality it is a journey into the ‘labyrinth of the human soul’. With a good dose of sheep as well.

The writing is simply first class. Laxness’ voice is simple and wry and filled with black humour, weaving Icelandic folklore and child-like imagination into a world of grim hardship. He is a true poet. The rest of the Laxness I’ve read has been translated by Magnus Magnusson, but I prefer J. A. Thompson. The vocabulary is richer and the style is smoother. I haven’t read the original so I can’t really comment on whether Magnusson’s or Thompson’s is closer to the spirit of Laxness, but I suspect (or hope) the latter is.

Independent People is an epic tragedy, filled with melancholic despair and great suffering (physical and emotional), but to me the book was not depressing, despite the fact that it did, and still does, make me cry. The story and the writing are beautiful and contain moments of great joy, humour and love alongside the tragedy. The characters are just perfect, and Bjartur must be one of the most interesting and complicated protagonists I’ve ever encountered. Every time I read it I am overwhelmed. Literature at its best: I can’t believe that anyone could come away from this untouched. I have read several other Laxness novels, but this is undoubtedly his masterpiece. It is a travesty that it is so little known; Independent People is one of the great modern classics and, to paraphrase Leithauser, this novel genuinely is not just good, not just great, but the book of my life.

Willem van de Poll, 1934

Angus’ perspective on IP:

Of sheep, lungworm, coffee, and poetry, and God, and a lot, lot more –

For some time now, I’ve been itching to write something about this wonderful, funny, lyrical, all-encompassing book. And now that I have a few moments to devote to it, I realize that I cannot put into words my love for this. The only thing that I can do is to keep shoving this to people with whom I share the similar taste in books.

But really, how can I justify the magnificence of this masterpiece if all I could tell them is that this book is all about sheep? It’s about farmers discussing and debating the different aspects of sheep farming while drinking coffee. It’s about them figuring out how to get rid of lungworm from the flock while discussing a little politics here and there. It’s about them worrying about the coming winter and hoping that their sheep will survive. And oh, it’s about the fierce battle of the unwavering independent spirits of a father and daughter. It’s a war waged between these two independent people. And I’d like to do a little background.

Bjartur of Summerhouses, the father that I mentioned, works his way out of servitude by saving money for almost two decades. When he earns enough money, he buys a piece of land that is believed by the townspeople to be cursed by some mad, evil, crazy woman. Bjartur, being one of the most iron-willed characters that I have ever encountered, ignores this. He builds a little house, starts raising sheep, marries a not so bad dame, and builds a family.

And the struggle for independent living goes on. Independent people, like myself, know the ups and downs of having to rely on your own resources to survive. Sometimes, the odds are with you. The good times keep rolling. You have coffee and sugar and dried fish in your stock. Sometimes, things are just bad. Sheep get lost, sheep get lungworm, sheep die. But when things are good again, the kids get some homeschooling. They study literature, geography, and catechism. A funny thing that I remember is that Little Nonni, the youngest son of Bjartur and my favorite character, imagines apples as red potatoes. Aren’t there apple trees in Iceland? The matter of apples was brought up when the kids’ teacher taught them all about Adam and Eve.

Fourth day: “Then why did God allow sin to enter the world?”

At first the teacher seemed not to have heard this question; he lay for a good while staring blindly in front of him, as if in a trance, a thing that occurred more and more frequently every day now; then suddenly he sprang up with a startling abruptness, gazed intently at the girl with huge eyes, and repeated questioningly: “Sin?” then he burst into a long fit of coughing, a deep, toneless, rattling cough; his face grew red and finally almost blue, the veins swelled in his neck, his eyes filled with tears. And when at last the fit was over, he dried his eyes and whispered breathlessly:

“Sin–sin is God’s most precious gift.”

So you see, this is not only about sheep. There’s a little talk on God and existence and the universe and who-are-we-what-is-our-purpose. There’s also some war in it, but since Iceland is mostly an observer when the world staged wars in the past, you get this feeling that our sheep farmers are isolated, only discussing among themselves the economic advantages that they might reap out of it. With coffee, of course.

And I lest I forget an important character, I’ll introduce her now: Asta Sollilja. She is the cross-eyed stepdaughter of Bjartur and the only person left to Bjartur thanks to his stubborn fight for independence. This is a strangely beautiful thing for me. You see, Bjartur has three sons, but he chose to let them go and favor the daughter that wasn’t his own in the first place.

Aside from his iron will, Bjartur also has a stone heart. He can get on your nerves, what with his repetitive talk that hey guys, I’m an independent person, I bought this land, I bought my sheep, I feed my family, I serve you coffee that I bought with my own money. And he would never ask anyone else’s help, even if it would make his family sacrifice and suffer, and even if it would cost them their lives.

But I am drawn to him. He is a poet! He recites Icelandic poetry. That, I think, is Bjartur’s most redeeming quality. And he is like a crustacean of a father; hard outer shell, soft innards. For why would Asta Sollilja, another stubborn spirit, finally go home to him and seek that soft spot on his father’s neck? Yes, at the end, Bjartur loses almost everything, all his three sons, but he has Asta Sollilja, a name that has something to do with a flower. Yes, I cannot remember what exactly that is. Perhaps the flower of his life?

5 stars - it was amazing and can one be truly independent as Bjartur is obsessively trying to be? I don’t think so. People are supposed to help each other, to be there for each other. Especially family. And we are social beings, for crying out loud. We cannot do it all by ourselves.

Bjartur learns his lesson and realizes the flaws of his ways. It’s always like that, isn’t it? We only realize our errors when everything is said and done. But we do not mock Bjartur. We do not tell him it’s all your fault, you and your goddamn pursuit of independence.

Instead, he earns our respect. We root for him even though we know he is prone to acts of stupidity. We forgive him for the things that he lack. We hope that he could still raise good sheep despite the harsh Icelandic landscape. And I think he could. He is one tough sheep farmer after all.

Farm with turf house, 1858, via Þjóðminjasafn Íslands

Darien’s epiphany after visiting Iceland:

I began this book over a year ago, and after many fits and starts just couldn’t get into it. I took it to Iceland with us and reading it there allowed the book to grab a hold of me. Independent People is quintessential Laxness. It evokes an era of Icelandic history that has past, and brings that era to life with grace and power. Visiting the area where the story takes place, in the south near Vík, it was very easy to imagine the people who eked out a living there a hundred years ago.

The story features an irascible sheep farmer, Bjartur of Summerhouses. He is short-sighted when it comes to the people around him, yet has a strong and unyielding vision regarding his place in the world—his place as a man who owns land and sheep, a man who is dependent upon no one. Unfortunately this vision is battered time and time again by circumstance. Iceland at the beginning of the twentieth century is a hard, unforgiving land, and social equity is not on close terms with the poor. Despite the tragic undertones inherent in the plot, the characters are drawn with great originality and humor in true Laxness fashion.

Bjartur is fearlessly direct in his dealings with the people who make up his world, whether they be rich or poor, honest or shams. Bjartur is “determined to meet everything with equanimity.” The Bailiff, who is a man of much stature in the community, responds to Bjartur's plain language by saying, “Yes, old boy...you always would have your little joke, wouldn’t you?” Yet Bjartur doesn't dissemble or trifle with others; he shows very little evidence of humor. He is single-sighted in his pursuit of maintaining his independence and caring for his beloved sheep, and when he sacrifices everything—including his family—in pursuit of these goals it is hard not to despise him. It is a credit to Laxness’ skill that he draws Bjartur so finely that you can’t hate him as you want to, because you understand him. Most authors buy your allegiance to their characters by allowing them to change, to become more as you might want them to be. Not so Bjartur! One is never disappointed by seeing him be less than true to his nature.

Delicate, tiny mosses grow in Icelandic lava, if you look closely. You will find some little beauty in Bjartur as well, beauty that is colorful, varied, subtle.

Has Halldór Laxness written a book that is less than perfect? How beautiful is his language? Try this:

It was the shortest day. The sky grew overcast during the morning, with low clouds, snow-charged and threatening, hanging half-way up the mountain slopes. No wondrous gleam lit soul or landscape; there was only a little midday no sooner come than gone, yet how much darkness was needed to wrap it round!

Frederick W. W. Howell, Hraun, 1900

[P] struggles with Independent People:

In 874 CE a Norwegian chieftain, Ingólfr Arnarson, became the first permanent settler on the island that came to be known as Iceland. Ah, truly an independent man! One can’t help but think that Gudbjartur of Summerhouses, the dominant character in Halldór Laxness’ Independent People, would have approved of such a state of affairs. As the novel begins, Bjartur has purchased his own piece of land, after working, for eighteen years, for the Bailiff. This is, despite the measly nature of the land and the shabby dwelling upon it, a momentous occasion for him; he is, at last, a free and independent person. Indeed, Bjartur prizes this independence above all else, so that it becomes almost a mania with him. For example: in the opening chapter there is told the story of the witch Gunnvor, out of which has grown a kind of superstition that one must, when passing her so-called resting place, ‘give her a stone.’ Bjartur, however, refuses, even when his new wife begs him out of a fear of bad luck. He would, it is clear, rather make her unhappy than compromise his principles, than for one moment sacrifice the smallest amount of his freedom [i.e. his freedom to act as he pleases]. Likewise, when she later yearns for some milk, he makes it clear that he will not countenance it because he cannot produce it himself. Bjartur will not ask for anything from anyone else, as he sees this as begging; nor will he accept gifts either.

One might wonder then how one is to approach Bjartur, what one is to make of him, for there are elements of his personality and behaviour that are agreeable and elements that are, in contrast, entirely disagreeable. First of all, we instinctively root for those who strive for freedom; as we do those who live in accordance with their principles, and those who are prepared to work hard. However, his behaviour has disastrous results for his family. Hard work, principles, ideals, freedom, all that is well and good, but if the result is overwhelming misery then one must question whether it is worth it, whether the man who brings down this misery upon his family [if one wants to say that he does – and you do not want to blame economic conditions] is not actually a good person. This, for me, is one of the key questions that the novel raises: just how important are principles? Are they worth sacrificing your health and happiness for? I must admit that I was never really sure how I felt about Gudbjartur of Summerhouses. He has many admirable qualities, and he is capable of tenderness, but he is equally capable of monstrosities.

It was pretty miserable wretches that minded at all whether they were wet or dry. He could not understand why such people had been born. “It’s nothing but damned eccentricity to want to be dry” he would say. “I’ve been wet more than half my life and never been a whit the worse for it.”

It is interesting in light of all this to consider that Laxness was, by all accounts, a Marxist. Indeed, he is said to have visited Russia prior to commencing work on Independent People and was very impressed. Even without this knowledge it is clear that with the novel Laxness was, to some extent, making a political statement. Throughout characters engage in political discussions, pass comment on the governing of the country, and wax philosophical about the status of the working man. Moreover, it is significant that the title is plural; Laxness is clearly not, therefore, only concerned with one resolute man, but, rather, an entire country or class. It is worth noting, in this regard, that from 1262 to 1918, Iceland was ruled by Norway and then Denmark, and that the country itself only became independent in 1918, shortly before the novel was written.

Yet if you accept that Laxness was concerned with an entire class or country, and one considers the Marxist sympathies, then his message seems somewhat obscure [although this may have much to do with my own ignorance]. Marx was himself concerned with labour, production, and the proletariat, all of which obviously play such a big part in the narrative of Independent People. For the German, giving up the ownership of one’s labour is to be alienated from one’s own nature, resulting in a kind of spiritual loss. This seems somewhat in line with how Bjartur is presented, a man who certainly does own his own labour. However, Marx also advocated that the proletariat should have class consciousness, that they ought to organise, and ultimately challenge the prevailing system, which is not at all in keeping with Bjartur’s behaviour and opinions, as he is suspicious of political engagement and, well, men-at-large. For example, when the Bailiff’s son, Ingolfur, broaches the idea of a Co-operative Society for farmers, which would, he claims, prevent exploitation, Bjartur isn’t at all interested.

If Bjartur was intended as some kind of anti-capitalist hero then the book fails, because he is not necessarily against capitalism (he defends the merchant), he is simply against anything or anyone he deems to be in some way attempting to deny him freedom or independence. For Bjartur, one can be as ruthless and money-grubbing as one likes as long as you don’t interfere with him. Moreover, this free man, this man who owns his own labour, only ends up exacerbating the suffering of innocent people. As the novel progresses, the reader may legitimately ask if he, or certainly his family, wouldn’t have been better off remaining in the pay of a wealthier employer, if that wouldn’t be a more comfortable and, therefore, rational way of living. In fact, while one might look to the Bailiff and his wife – who periodically appears in the text in order to make glib and patronising statements about the working class, about how only poor people are truly happy, and how much she envies them. She contrasts this, of course, with the hard life of being a bourgeois employer, where all your money goes on paying wages and one cannot [the horror!] afford that dress you’ve had your eye on for a while – as the capitalist villains of the piece, the more I thought about it the more I realised that Bjartur himself could be called a capitalist, just not in the way that we tend to understand that term these days.

When someone says ‘capitalist’ we (or certainly I) tend to imagine someone rich, with at least one thriving business, which is run on the toil of hired workers. Well, Bjartur is categorically not rich; nor does he own a thriving business; and the only workers he has are his own family. Yet his situation is a capitalist model; his farm, although not at all flourishing, is a private enterprise and his family are absolutely exploited as a means of production. The kids, the wife, all are expected to put in extremely long hours, and far from being rewarded commensurate to their efforts are actually given very little to eat, live in wretched circumstances [a small, foul-smelling, leaky hut] and have only rags to wear; indeed, these workers are actually sacrificed in order to protect the business’ assets [i.e. the sheep, which are given preferential treatment]. It is likely that I am wrong about all this, as I am admittedly no expert on Marxism and so on, but It was only when this interpretation came to me that the politics of the novel started to make more sense. Marx wrote about the ‘despotism of capital,’ and that phrase could be seen to sum up this book.

I worry that so far I have made Laxness’ work seem horribly dry and grim and unapproachable. I mean, it is grim, there’s no way of getting around that, but it is not without warmth and humour and beauty either. Bjartur, although a kind of tyrant, is also a funny character, particularly in the opening stages of the novel; and even when things are at their blackest there are still moments of absurd comedy, for example, when Bjartur says, “A free man can live on fish. Independence is better than meat.” Furthermore, there is some fine nature writing which acts as a contrast to the unrelenting drudgery. In fact, Laxness’ prose is what makes the novel bearable. I dislike throwing the word ‘poetic’ around because I think it is often used merely as a way of describing so-called superior or flowery writing. It is apt in this case; the Icelander was, I believe, actually a poet; and, well, it shows.

Shortly afterwards it started raining, very innocently at first, but the sky was packed tight with cloud and gradually the drops grew bigger and heavier, until it was autumn’s dismal rain that was falling—rain that seemed to fill the entire world with its leaden beat, rain suggestive in its dreariness of everlasting waterfalls between the planets, rain that thatched the heavens with drabness and brooded oppressively over the whole countryside, like a disease, strong in the power of its flat, unvarying monotony, its smothering heaviness, its cold, unrelenting cruelty. Smoothly, smoothly it fell, over the whole shire, over the fallen marsh grass, over the troubled lake, the iron-grey gravel flats, the sombre mountain above the croft, smudging out every prospect. And the heavy, hopeless, interminable beat wormed its way into every crevice in the house, lay like a pad of cotton wool over the ears, and embraced everything, both near and far, in its compass, like an unromantic story from life itself that has no rhythm and no crescendo, no climax, but which is nevertheless overwhelming in its scope, terrifying in its significance. And at the bottom of this unfathomed ocean of teeming rain sat the little house and its one neurotic woman.

Moreover, as with all great novels of some heft, there are certain scenes in Independent People that will likely stay with you long after reading the book. For me, there are two in particular. First of all, there is the chapter when Bjartur leaves his wife Rosa on her own overnight with his favourite gimmer [one of the Rev. Gudmundur’s breed, no less!] as company. Rosa, who has been on edge ever since not being allowed to give Gunnvor a stone, sees in the sheep’s frightened bleating some kind of evil omen. Laxness takes this potentially ridiculous set-up and manages to imbue it with a creeping tension and horror, until Rosa finally snaps and executes the gimmer. It is, in my opinion, one of the most powerful descriptions of madness in literature. The other big favourite of mine is when Bjartur goes in search of the sheep (for he doesn’t know it is dead) and spots a group of reindeer. He decides, being a strong-willed independent man, that he is going to capture the buck for meat. This is no easy feat, of course. During the struggle, he climbs upon its back and the buck takes him into the river Glacier in an effort to throw him.

When I read another of Laxness’ most well-known works, World Light, last year, I felt as though the characters lacked depth; it struck me that they had a signature mood or quirk, and that is all. As I reread Independent People I was starting to get the same feeling about Bjartur; yes, he has a mania for independence and freedom…I get all that, I enjoy it, but one reaches a stage where this point has been hammered home so frequently in the first one hundred pages that you start to worry about another four hundred of it. What sets this book apart from World Light, and many other lesser novels, is that Laxness knew when to change it up. So when Bjartur’s one-man show (he has a wife, of course, but she’s only really there for him to harangue about independence) starts to creak a bit, when it’s becoming repetitive, the author introduces a number of interesting new characters. In a way, one could criticise this move, for it is so abrupt, but providing Bjartur with a new wife, mother-in-law, and children, it gives the book fresh impetus. Moreover, this family is more finely crafted, have a greater emotional range and a more sophisticated inner life; this is particularly true of the children, Nonni and Asta, who are wonderful creations.

I’ve never been one for child worship, for finding a child’s misfortune worse than any other; I find that attitude quite odd, in fact; but Asta, Bjartur’s daughter from his first marriage, ruined me. She was born in extraordinary circumstances, tragic circumstances, and her life at Summerhouses proceeds in a manner no less tragic. There are numerous books that have moved me, many that have needled my personal sore spots (which this one does too, actually – anything to do with poverty tends to affect me emotionally), but this, as far I can remember, is the only book ever to make me cry, to provoke a tear into dribbling miserably down my cheek. And it is all Asta’s fault. I’m not even sure why she got to me so much; she’s a sensitive, trusting slip of a girl, who, in her naivety or innocence, wants so little (her joy at being given an old worn dress of her mother’s all but finished me off), but, crucially, unlike her father, she does want; she is inquisitive, eager to learn. Maybe it is that: desiring such meagre or basic things, and being denied them. Or perhaps it is simply that having been brought up by a struggling single mother I just can’t bear to see women unhappy. I don’t know.

It is worth noting, in conclusion, that, after all the exhausting and frequently oppressive bleakness, there is, towards the end, a tiny shaft of light, a few whispered comforting words that suggest that love, at least, will endure. Ah, hold onto those words, store them in your heart, because a little hope, even blind hope, is the most precious thing of all.

Frederick W. W. Howell, Húsavík, ca. 1900

Lucy’s analysis of Independent People and Halldór Laxness:

I started to read Patrick White’s Tree Of Man, but having spent the past nine years writing a novel about a young couple living in an isolated bush hut, I found myself unable to bear White’s setting - a young couple in an isolated bush hut. I mentioned this to our flatmate, Tony, and he said, “Then you wouldn't be interested in reading a novel about a family living in an isolated hut in Iceland.” Perhaps guided by the spirit of contrariness, or else by my summer habit of reading books set in snowy places, I borrowed Halldór Laxness’ Independent People.

I was immediately won over by Laxness’ tone. Rural culture is very attractive to writers, not only because it’s usually an exotic culture for anyone who spends their time stuck inside at a desk writing (and trying to get what they write published), but also because it is a good frame for that perennial theme of ‘What have we lost or gained in adopting modern life?’ There are plenty of writers who have thoroughly researched rural culture, and get all the details right, and many who use an insightful understanding of it to make some good points, but few who can write about rural culture from within. Thomas Hardy and Halldór Laxness are the best I've come across. They provide the reader with all sorts of fascinating and obscure details, and they are worldly enough to contrast traditional life with modern life. But their sharpest tool is their ability simultaneously to criticise and praise rural culture. This seems to be the proof of thoroughly knowing one’s subject. I think of how the trait that most irritates us about a beloved friend is also often the one we most admire; it’s because this trait is strong, distinctive, notable, and we have suffered at its hands.

In Independent People, and Hardy’s novels, there is a lot of suffering—detailed suffering. Because of the suffering, these writers know that this way of life should and will end; yet they value it enough to document it before it disappears. I keep thinking of the conversations the crofters have on the rare occasion of a get-together: although epic poetry might be momentarily touched upon, the recurring topic is parasitic worms. Laxness's sheep-farmers have much to say about worms, and it's not uninteresting. Sometimes, such as when they gather at the farm of Bjartur, our independent man, to see evidence of the gruesome sheep-massacre possibly perpetrated by a ghost, I was relieved when their conversation left the spooky, and reverted to the here-and-now of worms and sheep - the staff of life for the independent crofter. But we, like Bjartur's children, who know there's more to life, suffer at the hands of the prevailing worm and sheep obsession, and long for beauty, love, anything else! Another writer would carefully recreate authentic-sounding sheep-crofter conversations, admiring the earthiness, immediacy, depth of knowledge; yet another writer would depict the oppressive and maddening narrowness; but Laxness presents the reader with both angles and a few in between.

Often when a writer views a subject equivocally, it results in a coolly dispassionate tone - a kind of balancing act that ends up neutral. There’s nothing neutral about Laxness’ novel; it’s full of extremes. There’s a description of the farm in summer, where the whole family is harvesting hay for eighteen or more hours every day, and it’s raining constantly, and everyone is sick (except the iron-clad Bjartur), with their noses streaming, forever hungry, one or another of them falling asleep in the wet grass with a load of hay on their back, the mother slowly dying of overwork and malnutrition. It’s a horrific description of ‘summer in Iceland’, a time of year I would have thought beautiful and a respite. Later, it is contrasted with summer in Bjartur's valley as viewed by a well-heeled young man who camps there for pleasure over a week or two. Through the young man’s eyes, Bjartur’s valley is Paradise. Laxness is capable of seeing it as heaven and hell—both at once.

The main character in Independent People is Bjartur, the most staunchly independent person of the whole lot. He sacrifices almost everything for the sake of independence—two wives, several children. Laxness somehow manages to pull off the balancing act even with this character, whom you couldn’t exactly call the hero of the novel. Bjartur is a tyrant, who commits some unforgivable acts (such as slaughtering the beloved family cow); but somehow we don't hate him. He has a certain integrity, even if he is lacking in kindness. And he is driven by a dream—of being an independent farmer, owing nothing to anyone—and we like dreamers. We know there's more to Bjartur than sheep-and-worms. Laxness's ending is truly beautiful: Bjartur’s dream is scuttled, he is forced to compromise and is redeemed. In novels, I love the redemption ending—the whole, long novel existing to bring to life the moment of redemption.

The most remarkable thing about man's dreams is that they all come true; this has always been the case, though no one would care to admit it. And a peculiarity of man’s behaviour is that he is not in the least surprised when his dreams do come true; it is as if he had always expected nothing else. The goal to be reached and the determination to reach it are brother and sister, and slumber both in the same heart.

A couple of pages later:

Everything that one has ever created achieves reality. And soon the day dawns when one finds oneself at the mercy of the reality that one has created; and mourns the day when one's life was almost void of reality, almost a nullity; idle, inoffensive fancies spun around a knot in a roof.

Independent People has many passages I could have dog-eared (I’m reluctant to dog-ear a borrowed book) for their sheer beauty. The lyricism of the writing—which in this case is the characters’ thoughts and feelings and observations—is probably the only reason anyone can bear to read nearly five hundred pages of abject hardship. The lyricism is like the novel’s oft-repeated motif of ‘the flower among the rocks’.

Here’s an exchange between Bjartur’s daughter (the flower of his life) and the young man who camps in the valley:

“What do they call you?” he asked, and her heart stood still.

“Asta Sollilja,” she blurted out in an anguish-stricken voice.

“Asta what?” he asked, but she didn’t dare own up to it again.

“Sollilja,” said little Nonni.

“Amazing,” he said, gazing at her as if to make sure whether it could be true, while she thought how dreadful it was to be saddled with such an absurdity. But he smiled at her and forgave her and comforted her and there was something so good and so good in his eyes; so mild; it is in this that the soul longs to rest; from eternity to eternity. And she saw it for the first time in his eyes, and perhaps never afterwards, and faced it and understood. And that was that. “Now I know why the valley is so lovely,” said the visitor.

I dog-eared this passage partly because I found it beautiful, but also because there is something sweetly teen-aged and romantic about it. As a youngish female writer, I sometimes feel shy of writing passages that have a teen-aged, romantic scent about them. As I was editing my recently-finished manuscript with my father, he urged me to excise anything that showed tenderness (he would say sentimentality) towards children (e.g. “wide-eyed”), or, worse still, animals (he wanted me to get rid of all sightings of kangaroos). We struck compromises, and he was probably right. But I was reading Anna Karenina at the time, which is full of sentimental and touching descriptions of children; I’m positive they were sometimes wide-eyed. Children are! Geoff’s riposte was irrefutable: “You're not Tolstoy.” However, I have a lingering resentment of the fact I’m not a dignified old man who can write the occasional soppy bit and be all the more loved and respected because of it. I just need to win a Nobel Prize (as Laxness did).

I’ll end with a poem that appeared in the novel. I don’t know whether it is a traditional Icelandic song, or Laxness’ own composition:

When the fiddle’s song is still,

And the bird in shelter shivers,

When the snow hides every hill,

Blinds the eye to dales and rivers,

Often in the halls of dreams,

Or afar, by distant woodland,

I behold the one who seems

First of all men in our Iceland.

Like a note upon the string

Once he dwelt with me in gladness.

Ever shall my wishes bring

Peace to calm his distant sadness.

Still the string whispers his song;

That may break, a love-gift only;

But my wish shall make him strong,

Never shall he travel lonely.

Tamara is profoundly touched by Independent People:

Situated in Iceland’s unforgiving climate and rugged terrain and against the backdrop of Iceland’s struggle for independence in the early twentieth century, Halldor Laxness’ Independent People explores complex issues of survival, independence, and community. This masterpiece secured for Laxness the 1955 Nobel Prize in Literature.

The protagonist is Bjartur of Summerhouses, a stubborn, opinionated, inflexible, and fiercely independent sheep farmer who exhibits a mass of contradictory qualities. Bjartur is compassionate, tender, solicitous, and considerate. But only if you happen to be one of his sheep. By contrast, his treatment toward his family occasionally borders on cruelty. He expects them to whip themselves into shape as he has done, survive on stale fish and endless cups of coffee, confront the harsh Icelandic winters with equanimity, and vehemently decline assistance from others. Bjartur values his independence above all else, even at the expense of exposing his family to severe hardship. He disdains the most basic comforts in life and expects his family to do the same.

The story unfolds as Bjartur, having labored for eighteen years for others, finally secures a home for himself and his sheep. His first wife dies giving birth to Asta Sollilja, a girl he knows is not his. His second wife moves into his croft with her mother. She produces several children, only three of whom survive. She dies of grief when Bjartur ignores her pleas and kills the one meagre cow they possess. His eldest son walks out in a snow storm one evening and is never seen again. He ousts his only daughter from home on a freezing night when he discovers she is pregnant.

World War I brings prosperity to Icelandic farmers. Bjartur builds a home for himself only to lose it like many others before him because he is unable to pay his debts. His world disintegrates and he is forced to relocate to his mother-in-law’s home. The novel ends on a note of reconciliation. Bjartur finds Asta Sollilja living in a hovel with her two children. She is weak, coughing blood, and dying of consumption. He sweeps her up with her children and takes her home.

There is much to love about Bjartur. He writes poetry and recites Icelandic sagas, claiming their heroes as a point of reference in his every day conversations. His determination to be self-reliant is heroic. He works hard and expects others to do the same. He is a man of his word. He is noble, heroic, stoic, and proud. But there is also much about him that frustrates. He is incorrigible, fixated on his one goal, harsh in word and deed, and oblivious to the adverse effects his intransigence has on his family. It is almost as if he feels the need to suppress his emotions in order to survive in an inhospitable climate. His layers of tough skin peel away at the end of the novel, revealing his ability to forgive and to love another deeply as he carries his dying daughter, “the one flower of his life,” to their new home.

In Independent People Laxness has produced a novel vast in scope and epic in nature. At the center of this masterpiece is a complex, fascinating protagonist. Laxness’ language is poetic, beautiful in its simplicity, full of profound insights, laced with irony and understated humor, and smattered with references to Icelandic heroes and mythological characters. At times his prose leaves you breathless. The characters are so real, they could almost walk off the page. His detailed descriptions transport the reader to the expansive moors and the modest croft; to experiencing the biting cold and relentless snow storms; and to smelling and hearing the sheep, the sheep, the sheep in all their tapewormy glory.

This is more than a novel about an Icelandic sheep farmer struggling to survive. This is a deeply profound masterpiece about the struggles we face in life. It is full of beauty, full of sadness, and brimming with poetry and wisdom. It is a novel that speaks to our common humanity and touches the soul.

Very highly recommended.

First posted on the website of Tamara Agha-Jaffar, used by permission.

Jorge’s excellent video review of IP:

Ann's YouTube endorsement:

Beejay’s holiday entrancement with Bjartur and IP in The Monthly Magazine…

Vintage Pages looks at Laxness’ ‘devastating critque’ …

Efe’s essay on a ‘Hard and Necessary’ book…

John’s introduction to IP from Literary Hub…

Annie’s NYT review of IP…

Peter’s look at IP at Arrowsmith Press…

Charlie breaks down IP and Salka Valka in The Baffler…

Dorothy looks at the “grimly comic“ Independent People…

Beth’s review and thread at World Literature Forum…

Marc’s extended discussion of Independent People re: Socialism…

Victoria reviews IP…

Jane’s recommendation in The Chicago Tribune…

Bruce’s 1946 review in The Atlantic…

Charlemange uses Bjartur's dilemma as a metaphor for modern finance…

Andrew’s take on Bjartur and IP…

Jayan’s impressions on People…

Raj recommends Independent People…

Christina says you must read this novel…

Jacob compares and contrasts IP with Wendell Berry…

Suzi’s poetic impression of Independent People…

Claudio looks at IP from an Italian perspective (Google translated)…

Kate’s pattern inspired by Ásta Sóllilja (for knitters)…

Sam’s Grapevine piece on Laxness and IP and Brad’s response to it…

Torrey’s obsession with Independent People in the Publishers Weekly…

Jonathan’s look at IP from down under…

Shoshi takes on Laxness and IP…

Jonathan’s reaction to the ending of IP…

Sujatha’s shouts out to HKL in the Q&A of Tyler Cowen’s interview…

John’s review in his Fionnchu blog…

David’s WNYC podcast review…

Marilyn’s books, with IP at #117…

Eiríkur reports on a modern edition of IP for young people…

Barbara relates story of being gifted IP by Ann Patchett…

Peter ruminates on IP…

Elizabeth’s povpodcast on Independent People…

Gemma shares her frustration with Bjartur…

Fiction Beast covers IP in video review…

Orrin’s 20th century review of IP…

Rachel’s must-read book on human rights…

The Transcendentalist’s Substack essay on IP…

Alison’s Five Books recommendation…

John sees the heroic in the everday in Independent People…

Chiara looks at IP from an Italian POV (Google Translate)…

Teresa discovers “breathtaking” IP…

Cillian recommends IP…

Bormgan’s radar picks up on IP…

Various reviews of Laxness in Read the Nobels…

Reddit thread on IP…

English Literature Teacher’s 4 part series on IP…

Visit the site that “inspired” Independent People…

Publishing history:

Sjálfstætt fólk (Part I) - Landnámsmaður Íslands, 1934

Sjálfstætt fólk (Part II) - Erfiðir tímar, 1935

Translated by J.A. Thompson:

Independent People

Allen & Unwin, London, 1945

Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1946

People’s Publishing House, 1957, New Delhi

Greenwood Press, 1976, Westport, CT

Vintage International, New York, 1997, introduction by Brad Leithauser

Harvill Press, London, 1999

Vintage Classics, New York, 2010

Random House Everyman’s Library, New York, 2020

Penguin paperback, 2022, eBook, 2010

At first the teacher seemed not to have heard this question; he lay for a good while staring blindly in front of him, as if in a trance, a thing that occurred more and more frequently every day now; then suddenly he sprang up with a startling abruptness, gazed intently at the girl with huge eyes, and repeated questioningly: “Sin?” then he burst into a long fit of coughing, a deep, toneless, rattling cough; his face grew red and finally almost blue, the veins swelled in his neck, his eyes filled with tears. And when at last the fit was over, he dried his eyes and whispered breathlessly:

“Sin–sin is God’s most precious gift.”

“Asta Sollilja,” she blurted out in an anguish-stricken voice.

“Asta what?” he asked, but she didn’t dare own up to it again.

“Sollilja,” said little Nonni.

“Amazing,” he said, gazing at her as if to make sure whether it could be true, while she thought how dreadful it was to be saddled with such an absurdity. But he smiled at her and forgave her and comforted her and there was something so good and so good in his eyes; so mild; it is in this that the soul longs to rest; from eternity to eternity. And she saw it for the first time in his eyes, and perhaps never afterwards, and faced it and understood. And that was that. “Now I know why the valley is so lovely,” said the visitor.

And the bird in shelter shivers,

When the snow hides every hill,

Blinds the eye to dales and rivers,

Often in the halls of dreams,

Or afar, by distant woodland,

I behold the one who seems

First of all men in our Iceland.

Like a note upon the string

Once he dwelt with me in gladness.

Ever shall my wishes bring

Peace to calm his distant sadness.

Still the string whispers his song;

That may break, a love-gift only;

But my wish shall make him strong,

Never shall he travel lonely.

4 Comments:

My uncle, James Anderson Thompson, translated Independent People and it was the work of his life. He spent years completing the work; his attention to detail was all-consuming. To the frustration of publishers Allen and Unwin his transcription was submitted to them in minute writing in school exercise books. The flow of the work was interspersed with protracted communications between Jim and Laxness to unravel the exact meaning in small details. Based on his attention to detail I would say that Jim's translation must be the truest of any of Laxness' work into English. I know that Laxness himself was very pleased with it.

Thank you for sharing your unique perspective with us. One thing I’ve discovered in reading Laxness in translation is that there are times when I feel that I’ve been left ‘hanging’—the subtle meaning of a phrase has been lost. Not so with Independent People, your uncle’s masterpiece of translation.

I was suggested to read by Lawrence Millman....fits and starts, couldnt get into it, for years....in Russia, I took to it nonstop. At age 49. Towards the end, I began to fret: what the hell to do afterwards? Now I didnt want it to stop. Maybe the best book Ive ever read and Ive read thousands.

Have you read any of the other novels by Laxness?

Post a Comment